La Familia Michoacana Drug Cartel

https://twitter.com/AntifaWatch2

http://antifaw26xsfwrt57feclcdzw4pkkn5wca2scrhrkltykabecpykndid.onion/

https://antifawatch.net/Browse/1La Familia Michoacana, (English: The Michoacán Family) La Familia (English: The Family), or LFM[3][4] is a Mexican drug cartel and organized crime syndicate based in the Mexican state of Michoacán. They are known to produce large amounts of methamphetamine in clandestine laboratories in Michoacan.[5] Formerly allied to the Gulf Cartel—as part of Los Zetas[6][7]—it split off in 2006.[6][8] The cartel was founded by Carlos Rosales Mendoza, a close associate of Osiel Cárdenas. The second leader, Nazario Moreno González, known as El Más Loco (English: The Craziest One),[9] preached his organization's divine right to eliminate enemies. He carried a "bible" of his own sayings and insisted that his army of traffickers and hitmen avoid using the narcotics they produce and sell.[10][11] Nazario Moreno's partners were José de Jesús Méndez Vargas, Servando Gómez Martínez and Enrique Plancarte Solís, each of whom has a bounty of $2 million for his capture,[12] and were contesting the control of the organization.[13]

In July 2009 and November 2010, La Familia Michoacana offered to retreat and even disband their cartel, "with the condition that both the Federal Government, and State and Federal Police commit to safeguarding the security of the state of Michoacán."[14] However, President Felipe Calderón's government refused to strike a deal with the cartel and rejected their calls for dialogue. According to federal and state sources, La Familia Michoacana has been increasingly involved in Michoacán's politics, impelling their favorite candidates, financing their campaigns, and forcing other parties to renounce their candidacies.[15][16] As of 2011, La Familia Michoacana still exists, mostly active in Estado de Mexico,[17][18] despite the killing of its founder and leader Nazario Moreno González.[13][19][20] Several leaders split off after his death to form the Knights Templar.[21

*********

ANTIFA Anarchist Terrrorists are SCARED of Criminal Street Gangs like the Crips in Long Beach, CA

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YKPG-d1uPmg

****************************************

Enjoyable Viewing: Crips Gang Members Kick BLM / ANTIFA Looters Out of Long Beach, California

In an age when gutless, namby-pamby progressive pantywaists are “too ‘fraid” to enforce law and order amid violent looters and Marxist-loving morons, you can count on the Crips to get the job done right.

In Long Beach, CA this week, Crips gang members allegedly through skinny-jean wearing looters out of their territory, eliciting heartfelt apologies from several of the “protesting bargain-hunters of peace” who think nothing of throwing bricks through store windows, or at cops’ heads.

Take a look! It’s delightful viewing to behold!

https://twitter.com/zerosum24/status/1278102174522892289?s=20

Who needs Kleenex?

WIBC’s Hammer and Nigel have more on the butt-kicking of Long Beach looters in today’s edition of “Are You Okay With This?”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JpDvDss_Is4

Chinese Triads Gang beat ANTIFA Anarchist Terrorist in Hong Kong

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vz8Id_v6b00

ANTIFA Anarchist Far Left / Leftist Marxist Communist Terrorists are SCARED of Motorcycle Clubs / Outlaw Biker Gangs like the Hells Angels and Gypsy Jokers

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a6gwqT8McUI

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a6gwqT8McUI

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5-YLZa63pUk

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VRTFgCe9pLU

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wBVkuJRT6G8

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x5bzgm_bY-4

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jiyh6fDBLug

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kO0FVaI5n5c

************************

Portland Antifa Picks Fight With Outlaw Bikers, Then Antifa Member Hailley Nolan Blamed Police When They’re Shot

Imagine the irony when the very same violent Antifa militants who spent the last two years promoting “Defund the Police” now blame those same police for not protecting them when their intended victims fight back.

Antifa in Portland apparently tried their bully tactics on the Gypsy Jokers motorcycle club over the weekend and things turned — surprise! — violent. In the end, with one dead and five more wounded (video), police try to put together just what happened.

Meanwhile Antifa is blaming the police, not themselves for the violence. At the same time, Antifa’s leaders are telling their members and people in general not to talk to the cops, and to pull down social media posts that contain photos and video of what happened…or else.

That sounds like witness intimidation, doesn’t it?

If police really were to blame for what happened, why isn’t Antifa falling all over itself to provide the evidence? After all, these violent extremists love to record their exploits.

The Post Millenial has the details . . .

A mass shooting late Saturday night has left one dead and five injured after Portland-area Antifa held a gathering in solidarity with Amir Locke, a 22-year-old black man who was shot by police in Minneapolis earlier this month.

A woman was pronounced deceased at the scene, and two men and three women were taken to nearby hospitals, according to the New York Times. Two suspects are reportedly in custody in response to the shooting, according to KPTV.

The shooting occurred at around 8 pm near Normandale Park.

Tweets from Antifa members and groups told far-left comrades that were present not to talk to police investigating the shooting, to delete evidence posted on social media, and to keep posts including photos, videos, and first-hand accounts related to the incident to a minimum “so that you don’t receive a knock.”

Antifa “journalist” Melissa Lewis, who was a co-plaintiff in a failed frivolous “Antifa troll” lawsuit filed in federal court against The Post Millennial‘s editor-at-large Andy Ngo, said that “[o]ne of us got a chunk of the shooter.”

https://twitter.com/MrAndyNgo/status/1551786810027671552

https://twitter.com/BernardPDXHRC/status/1548467446637465602

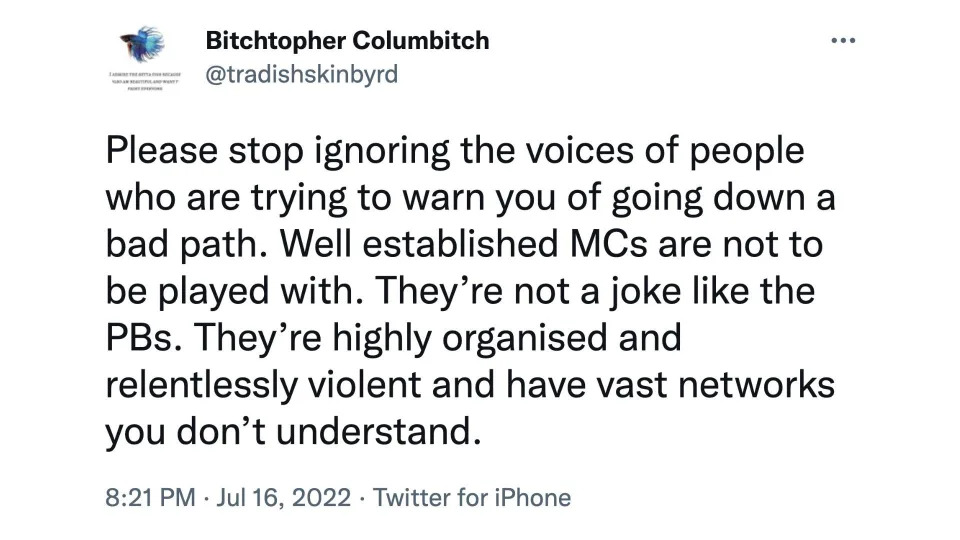

https://twitter.com/tradishskinbyrd/status/1548462871805190144

httphttps://twitter.com/MrAndyNgo/status/1551786810027671552?s=20s://twitter.com/MrAndyNgo/status/1551786810027671552?s=20 https://twitter.com/MrAndyNgo/status/1551786810027671552?s=20

Antifa in Portland apparently tried their bully tactics on the Gypsy Jokers motorcycle club over the weekend and things turned — surprise! — violent. In the end, with one dead and five more wounded (video), police try to put together just what happened.'

Antifa Hailley Nolan hijacked a Portland Police news conference the next morning and in an incoherent rant, blamed cops for the dead woman and the others who were wounded. The woman, Hailley Nolan breathlessly claimed that white supremacist cops are sending Gypsy Joker motorcycle club members to snatch Antifa members.

“They are sending Gypsy Jokers to kidnap us. They are sanctioning this violence against us. We are dying. We are trying to peacefully protest and they are killing us. And I want to know if any of you care. I want to know if Ted Wheeler cares.”

Local TV station KGW had this:

Hailley Nolan, an Antifa Anarchist Terrorist to Disrespects and Insults the Biker Gangs like the Gypsy Jokers

|

| Hailley Nolan, an Antifa Anarchist Terrorist to Disrespects and Insults the Biker Gangs like the Gypsy Jokers |

***********************

Anonymous Spokesman Flees Over Safety Concerns

https://www.seeker.com/anonymous-spokesman-flees-over-safety-concerns-1765504062.html

Though the jury's still out on the veracity of Anonymous' showdown with south-of-the-border bullies, Barrett Brown has emerged as the face of the hacktivist collective, which last week bit off possibly more than it could chew when it threatened the Mexican drug cartel Los Zetas.

Last week we told you how Anonymous drew a line-in-the-sand ultimatum, threatening to go public with the identities of local police, journalists, taxi drivers and other allies who conspire with Los Zetas if the cartel didn't release a kidnapped Anonymous member.

Though Anonymous apparently called off their Operation Cartel (#OpCartel) after Los Zetas allegedly returned the kidnapped victim, Brown has decided to flee his Dallas home over concerns for his security. On Nov. 8, he tweeted, "I've got ex-military people releasing info on me and family. Have to leave Texas."

According to a tweet, members of #OccupyDC picked up the tab for a plane ticket to New York City after Brown tweeted "Anyone who can buy me ticket to NYC/Boston and have me pay them back in month, let me know. Transistor@hushmail.com. Home no longer secure."

Perhaps fleeing to more northern exposures was a good move for Brown - especially after a Mexican man was found decapited and dumped in the town of Nuevo Laredo, one mile from the Texas border. The man's hands were handcuffed behind his back, his body and head publicly strewn on a bloody sheet of canvas scrawled with the message: "Hi I'm ‘Rascatripas' and this happened to me because I didn't understand I shouldn't post things on social networks."

*********************

Anonymous retreats from Mexico drug cartel confrontation

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2011/nov/02/anonymous-zetas-hacking-climbdown

Threats to begin unmasking members of Zetas reined back as cartel rumoured to be hiring own security specialists for physical retaliation – as others question whether Anonymous member was ever kidnapped in Veracruz

Plans by the hacker collective Anonymous to expose collaborators with Mexico's bloody Zetas drug cartel – a project it dubbed "#OpCartel" – have fallen into disarray, with some retreating from the idea of confronting the killers while others say that the kidnap of an Anonymous hacker, the incident meant to have spawned the scheme, never happened.

The apparent climbdown by the group came as one security company, Stratfor, claimed that the cartel was hiring its own security experts to track the hackers down – which could have resulted in "abduction, injury and death" for anyone it traced.

*********************

Motorcycle Monday: Portland Antifa members like Alexander Dial / @BetaCuck4Lyfe, Anthony Amoss, Clifford Phillip Eiffler-Rodriguez, Amanda Layla Woelfle (@tradishskinbyrd) and @BernardPDXHRC Declared War On Oregon Motorcycle Clubs / Biker Gangs

https://autos.yahoo.com/motorcycle-monday-antifa-declares-war-160000181.html

Back on Saturday, July 16 members of Antifa followed through on vows to try disrupting a gathering at the HonkyTonk Bar in Salem, Oregon. The result of the far-left group’s actions is what some are predicting to be a war between them and several motorcycle clubs throughout Oregon. If that sounds to you like a confrontation which would be wise to back away from, you’re not alone. What happens next could be ugly.

Watch the latest Motorious Podcast here.

Originally, Antifa groups began rallying members and supporters to join a “counter demonstration” for the “Take Action Tour” event being held at the HonkyTonk Bar. They characterized the venue’s gathering as “racist” and catering to both “fascists” as well as “white supremacists.” That event was marketed by the bar as “Hero Appreciation Day” complete with a dunk tank, bike show, eating contest, live music, bouncy house, family-friendly karaoke, free hot dogs, etc.

According to several Twitter posts from accounts journalist Andy Ngo says are Antifa members, the group which confronted them was the Free Souls Motorcycle Club. The one percenter motorcycle club might not have the household brand name of the Hells Angels, however its roots run deep. Founded in Eugene, Oregon in 1968 there’s considerable controversy over the details of its foundation, history, and what its aims are today. Regardless, Antifa seems poised to take it and other one percenter motorcycle clubs on in Oregon, promising for a confrontation like they’ve never seen.

White Rose of the Willamette Valley used its Twitter account to complain after Salem police didn’t protect their fellow Antifa members during the confrontation. It said Free Souls and “other uniformed security” both “attacked and injured community members peacefully protesting” without supplying details or other evidence. Unlawful whatever on Twitter claimed “one of ours” was hospitalized from the fight, retweeting a different person claiming “Salem police literally backed away” when the Free Souls came out to confront them. Another Antifa account proceeded to dox several people involved in the confrontation, tagging their supposed employers as well as releasing other personal details.

It's not like Antifa is unfamiliar with physical confrontation. Per Andy Ngo, one of the organizers of the demonstration at the HonkyTonk Bar was arrested in 2021 after allegedly hitting a female police officer. Ngo claimed another in attendance plead guilty the week before for doing over $164,000 in damages to a courthouse.

Anthony A. Amoss is an Antifa Anarchist Terrorist who wants to declare WAR against Criminal Street Gangs and Outlaw Biker Gangs

|

| Anthony A. Amoss is an Antifa Anarchist Terrorist who wants to declare WAR against Criminal Street Gangs and Outlaw Biker Gangs |

Clifford Phillip Eiffler-Rodriguez is an Antifa Anarchist Terrorist who wants to declare WAR against Criminal Street Gangs and Outlaw Biker Gangs

|

| Clifford Phillip Eiffler-Rodriguez is an Antifa Anarchist Terrorist who wants to declare WAR against Criminal Street Gangs and Outlaw Biker Gangs |

Alexander G. Dial @BetaCuck4Lyfe is an Antifa Anarchist Terrorist who wants to declare WAR against Criminal Street Gangs and Outlaw Biker Gangs

|

Alexander G. Dial @BetaCuck4Lyfe is an Antifa Anarchist Terrorist who wants to declare WAR against Criminal Street Gangs and Outlaw Biker Gangs |

Alexander G. Dial @BetaCuck4Lyfe is an Antifa Anarchist Terrorist who wants to declare WAR against Criminal Street Gangs and Outlaw Biker Gangs

|

Alexander G. Dial @BetaCuck4Lyfe is an Antifa Anarchist Terrorist who wants to declare WAR against Criminal Street Gangs and Outlaw Biker Gangs |

|

| Amanda Layla Woelfle (@tradishskinbyrd) is an Antifa Anarchist Terrorist who wants to declare WAR against Criminal Street Gangs and Outlaw Biker Gangs |

Amanda Layla Woelfle (@tradishskinbyrd) is an Antifa Anarchist Terrorist who wants to declare WAR against Criminal Street Gangs and Outlaw Biker Gangs

|

| Amanda Layla Woelfle (@tradishskinbyrd) is an Antifa Anarchist Terrorist who wants to declare WAR against Criminal Street Gangs and Outlaw Biker Gangs |

Nobody knows for sure what comes next in this feud, but some purported Antifa members took to Twitter to either voice their concern for the group’s trajectory or encourage others to push forward in that direction. One person warned Oregon motorcycle clubs are “highly organised (sic) and relentlessly violent and have vast networks you don’t understand.”

|

| @BernardPDXHRC wants the Antifa Anarchist Terrorists to fight against Criminal Street Gangs and Biker Gangs |

|

| @BernardPDXHRC wants the Antifa Anarchist Terrorists to fight against Criminal Street Gangs and Biker Gangs |

@BernardPDXHRC wants the Antifa Anarchist Terrorists wants to fight against Criminal Street Gangs and Biker Gangs

|

| Antifa Anarchist Terrorists wants to fight against Criminal Street Gangs and Biker Gangs |

Antifa Anarchist Terrorists wants to fight against Criminal Street Gangs and Biker Gangs

Hailley Nolan, an Antifa Anarchist Terrorist to Disrespects and Insults the Biker Gangs like the Gypsy Jokers

|

| Hailley Nolan, an Antifa Anarchist Terrorist to Disrespects and Insults the Biker Gangs like the Gypsy Jokers |

Antifa Watch - https://antifawatch.net/

Andy Ngo - https://twitter.com/MrAndyNgo

Andy Ngo - https://www.andy-ngo.com/

Andy Ngo - https://www.facebook.com/realAndyNgo

***********************

Darknet / Darkweb WARNING:

Download Tor, PGP Key, VPN

Enter at your OWN Risks.

Please use caution at all times.

Know who you trusts.

Never enter risky sites, attachments, files and links.

Never give your personal information

Use a separate computer, cellphone and Modem / Router for the Darknet Only

Use VPN and PGP Keys are all Times

Use Code Words and Encryption all Times

Disable Javascript

Buy, store and use cryptocurrency wisely

Bitcoin is BASIC. Monero is the BEST!!!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dxbsx1GrLSY

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zQW3MdF25B8

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FqgQhfE1bF8

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QrHsFZBab4U

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gki-8fFqhxQ

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aQJ9G0ChJh8

Darknet or Darkweb News and Insights:

Darknetlive - https://darknetlive.com/

DnStats - https://dnstats.net/

Secure World - https://www.secureworld.io/industry-news/topic/dark-web

Dark Fail - https://dark.fail/

Darknet One - https://darknetone.com

Darknet or Darkweb Tips:

Tor - https://www.torproject.org

Freenet - https://freenetproject.org

I2P - https://geti2p.net

Tails - https://tails.boum.org

Whonix - https://www.whonix.org

Cryptocurrency:

Cointelegraph - https://cointelegraph.com/

CoinDesk - https://www.coindesk.com

Coinbase - https://www.coinbase.com

Dark Web Search Engine

DuckDuckGo - https://duckduckgo.com

PGP Key:

The GNU Privacy Guard - https://gnupg.org

Gpg4win - https://www.gpg4win.org

PGP Tool - https://pgptool.org/

Attog - https://www.attogtech.com

PGP Key Generator - https://pgpkeygen.com/

PGP Key Generator 2 - https://wp2pgpmail.com/

Messaging App Alternatives:

Signal - https://signal.org/en/

Telegram - https://telegram.org

Kik - https://kik.com

Threema - https://threema.ch/en

VPN:

ExpressVPN - https://www.expressvpn.com

NordVPN - https://nordvpn.com

Surfshark - https://surfshark.com/

ProtonVPN - https://protonvpn.com/

PrivadoVPN - https://privadovpn.com

Windscribe - https://windscribe.com

AtlasVPN - https://atlasvpn.com/

Hide.Me - https://hide.me

Hotspot Shield - https://www.hotspotshield.com/

CyberGhostVPN - https://www.cyberghostvpn.com/en_US/

TunnelBear - https://www.tunnelbear.com

***********************

Social Media Alternatives for Facebook, Reddit and Twitter:

4chan - http://www.4chan.org

Minds - https://www.minds.com

Counter Social - https://counter.social

Panquake - https://panquake.com

Gab - https://gab.com

Mastodon - https://mastodon.social

Aether - https://getaether.net/

Steemit - https://steemit.com

Frendica - https://friendi.ca

Diaspora - https://diasporafoundation.org

MeWe - https://mewe.com

Peepeth - https://peepeth.com

Deso - https://www.deso.com

Revolt - https://revolt.chat

WireMin - https://wiremin.org

Evrylife - https://www.evrylife.org

Dragon Den - https://den.social

Tribel - https://www.tribel.com

Spreely - https://spreely.com

Mumblit - https://www.mumblit.com

Social Media Alternatives for Youtube:

Peertube - https://joinpeertube.org

Odysee - https://odysee.com

Rumble - https://rumble.com

Bitchute - https://www.bitchute.com

Lbry - https://lbry.com

Dtube - https://d.tube

Ganjing - https://www.ganjing.com

Freetube - https://freetubeapp.io

Dailymotion - https://www.dailymotion.com

Social Media Alternatives for Blogs:

Steemit - https://steemit.com

Lbry - https://lbry.com

Write - write.as

Social Media Alternatives for Instagram:

Pixelfled - https://pixelfed.org

Messaging App Alternatives:

Signal - https://signal.org/en/

Telegram - https://telegram.org

Kik - https://kik.com

Threema - https://threema.ch/en

Web Search Browser Alternatives:

DuckDuckGo - https://duckduckgo.com

Email Alternatives:

Protonmail - https://proton.me/mail

Mail IO - mail.io

Hive - https://www.hivesocial.app

Spoutible - https://spoutible.com

SafeChat - https://safechat.com

BONUS:

ZeroNet - https://zeronet.io

9 Gag - https://9gag.com/

Github - https://github.com/

Hacker Forums:

XSS - xss.is

Breached / RaidForums successor - breached.co

Dread - on the darknet

Nulled - nulled.to

Cracked - cracked.io

Exploit - exploit.in

PlusCC - pluscc.ws and pluscc.pw

Veracrypt - https://www.veracrypt.fr/code/VeraCrypt/

TrueCrypt - https://truecrypt.sourceforge.net

AxCrypt - https://axcrypt.net/

Disk Cryptor - https://diskcryptor.org/

GnuPG - https://gnupg.org/

Darknet / Darkweb Websites:

Hidden Wiki - http://zqktlwiuavvvqqt4ybvgvi7tyo4hjl5xgfuvpdf6otjiycgwqbym2qad.onion/wiki/index.php/Main_Page

Hidden Wallet - http://d46a7ehxj6d6f2cf4hi3b424uzywno24c7qtnvdvwsah5qpogewoeqid.onion/

Duck Duck Go - https://duckduckgogg42xjoc72x3sjasowoarfbgcmvfimaftt6twagswzczad.onion/

Dread Darknet Forum - http://dreadytofatroptsdj6io7l3xptbet6onoyno2yv7jicoxknyazubrad.onion/

Mail2Tor - http://mail2torjgmxgexntbrmhvgluavhj7ouul5yar6ylbvjkxwqf6ixkwyd.onion/

Haystack - http://haystak5njsmn2hqkewecpaxetahtwhsbsa64jom2k22z5afxhnpxfid.onion/

Onion Links - http://s4k4ceiapwwgcm3mkb6e4diqecpo7kvdnfr5gg7sph7jjppqkvwwqtyd.onion/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jT-jmq8KBw0

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-UEbOM5lNak

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pZH9ZYFU26U